March 26 to April 2, 2006

When I left my hotel in for my first morning of exploring Kabul the thing that most surprised me about the city was the weather. It was a rainy misty morning, a chilly drizzle was falling on the city. All my images of Afghanistan were of a hot, dry, dusty country. With the rain it was a day very like a typical spring day in my hometown Seattle. Of course the similarities stopped there. All the traditionally dressed men with full beards, turbans, and

shalwar kameez (the long baggy shirts, and pajama pants commonly worn all over Afghanistan and Pakistan) who looked like they just stepped out of National Geographic kept me from making any mistakes about where I was. Ok, I will admit, Kabul did have one other similarity to Seattle; the traffic was terrible.

I had very little Afghani, the local currency. So one of my first tasks in Kabul was to find a place where I could change some of my American Express traveler’s checks. At the hotel I was given the name and address of a bank. I caught a cab, but did not get far before we were mired in stop and go traffic. My cab driver was not typical of the cabbies I would meet in Kabul. He was young, clean-shaven, dressed in slacks and a sweater, spoke good English, was a university student, and drove a cab part time. He told me that the traffic in Kabul is always bad. Kabul is not actually all that large a city, but its population has swelled dramatically with the millions of refugees that have been returning since the fall of the Taliban. The population has swiftly overwhelmed the infrastructure. As a police cadet I would later meet put it, “Kabul is a city of three hundred thousand, with a population of three million.”

My cab driver had some difficulty locating the bank; he had to drive around the Wazir Akbar Khan neighborhood for a while before finding the correct street. There was no missing the bank when we did find it. It is not that the bank itself was distinctive; it was an unremarkable one-story building behind a high wall. It was all the concrete jersey barriers (for keeping cars from getting too close), barbed wire, and guards with assault rifles that suggested to me that there was something worth protecting, like a bank, here. Before entering the bank I had to pass through a metal detector, get patted down, and have the contents of my bag thoroughly searched. When I finally spoke to a teller it was only to be told that I could not exchange travelers checks without an account at the bank. The teller did offer that I could exchange my traveler’s check in the moneychangers’ bazaar in the old city.

Another cab ride and I was at Pul-e Khishti a, bridge on the outskirts of the old city. The old city lies to the south of the Kabul River. Here was the Kabul that is the exotic and foreign. Charahi Sadarat (the neighborhood where my hotel was) and Wazir Akbar Khan (where I was looking for the bank) are relatively sedate. They do not immediately seem so foreign. That is not true of Kabul’s old city. This is truly where Kabul belongs to the East. The intense throngs of people, bazaars of every variety, merchants shouting from all directions, the intense pulse of commerce. My interest was in the moneychangers’ bazaar. It was a little overwhelming and intimidating. I found a shop that would change traveler’s check, but I took a beating converting them to U.S. dollars. I had mostly $20 checks. The guy who exchanged my money said that lower denomination bills get a lower exchange. I do not know if I was getting screwed, but I did not feel comfortable spending too much time in the bazaar. Interesting, but I was glad to get out of there. This will be the last time I take travelers checks when I travel. In both Pakistan and Afghanistan they were difficult to exchange. Even in Afghanistan they have now have cash machines, so I no longer see the need to carry traveler’s checks.

Only in Kabul during daylight for a few hours I was zipping all over a city that I was not so sure I should be traveling around with such a cavalier attitude. I hated spending so much time on mundane chores like exchanging money. As I would find out of the next week I would waste a lot of time doing such mundane chores. I was being a little proud and trying to figure out everything on my own. Looking back, it would have been a far better use of my time to hire a local to drive me around and explain to me the ins and outs of the city.

I found this war-themed carpet on Chicken Street. Chicken street was a couple block of shops for tourists selling the usual crap: carpets, jewelry, and "antiques". Back in the 70's during the heyday of the hippie tourists, Chicken Street was a famous destination, but these days it seems a little sedate and never held much interest for me. Who these tourists are I have no clue. I was not sure who their customers were, I never saw any other westerners on Chicken Street. It was explained to me that all the major compounds (like the U.S. Embassy and ISAF) have bazaar day were the merchants are allowed to sell to Westerner within the safety of the compound walls.

It was on Chicken Street that I first gained some experience of Kabul beggars. There are quiet a few beggars in Kabul. Many are missing legs, which they lost to land mines. I saw some heart wrenching examples of destitution. One legless beggar is saw had to drag himself across the street on his belly, he did not even have one of those skateboard things I have seen a lot of legless beggars use. Some of the more fortunate ones had prosthetic limbs at least. There were a number of burqua-clad women with diseased or birth deformed children. Normally I do not like giving money to beggars, but in Kabul I am sure there is not any social safety net. However, giving money to a beggar has its risks. If others see you giving they will swarm you and you can be pursued down the street by close to a dozen beggars. I developed a quick donate technique, where I would give money to a beggar without stopping, hoping that others would not see me. I had mixed results with this.

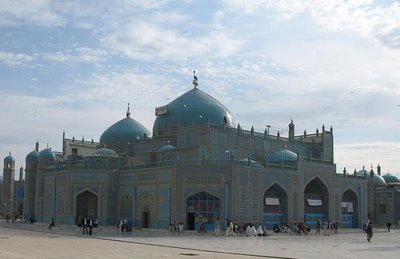

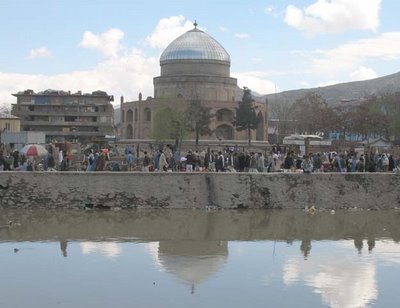

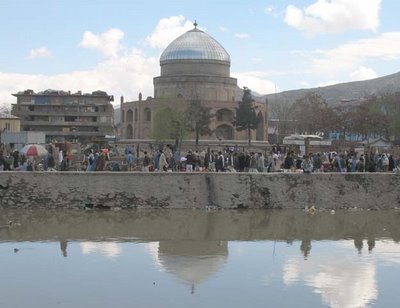

Although much of Kabul is ruined there are parts of the city that were untouched. Along the Kabul River near the Pul-e Shah-Doh Shamshira Bridge is the Shah-Doh-Shamshira Mosque. This mosque and the houses that line the Kabul River are among the untouched remnants that suggest the former charms of Kabul before the city was ravaged by twenty years of war. Thirty years ago Kabul was a cosmopolitan city that was popular with those adventurous tourists who made it to the Afghan capitol. It was the Eastern end of the "hippie trail" (Marrakech in Morocco being the Western end).

Every so often when walking around Kabul I would have one of those "I can’t believe I am really here" moments. After years of work on my novel, it was surreal to actually be in Afghanistan. I first got the idea for my novel in 1999. Since then I have been working on it in my spare time doing research, writing ideas, and taking writing classes. Finally, last year I wrote a rough draft. I liked what I wrote, but something was missing. I had squeezed every drop of information about Afghanistan out of the research material I had, but I wanted more. I wanted what I wrote to have more truth. I was looking for verisimilitude. I needed to see Afghanistan first-hand, not just through the filter of second-hand accounts.

A lot of people have asked me, "Why Afghanistan?" The answer is I did not choose Afghanistan, it chose me. The more research I did and the more I worked on my novel, the more fascinated I became with Afghanistan and its people. It is a country that appeals to the romantic in me. A poor, dry, barren land at the cross roads of the Mid-East, Central Asia, and South Asia whose fiercely proud people have humbled two super powers—it captured my imagination. I did not really have a specific agenda. My goals were very general. What I really wanted was just to get the feel for the place, you know, see the sights, eat the food, and meet the people. In 2003 I spent three weeks traveling in Morocco. That trip had a big influence on me and I got a lot of ideas for my novel from that experience. I was hoping to repeat that experience in Afghanistan.

One experience I did not have was meeting any Afghan women. This was similar to Morocco, another conservative Muslim country where the sexes do not mix. The heroine of my novel is Soraya, the beautiful widow who my hero John falls for. I was hoping to meet some Afghan women and from them take some deeper insight into the character of Soraya. The majority of women in Afghanistan are veiled, but many of the younger women went unveiled (but still wearing at least a shawl over their head). About the limit of my contact with women in Afghanistan were those that I passed on the street. It would have been dangerous to stare, but occasionally I would steal a glimpse at a young woman. I would see a dark-haired, light-eyed, olive skinned beauty and think, "Yes, she could be Soraya."

I often took cabs around the city. It was cheap, usually between 50 and 100 Afghani ($1 to $2). I never had any problems, but I could not help thinking how vulnerable I was in a cab. Everyone in Kabul has a cell phone and it seemed like every cabbie I got a ride with was constantly talking on their phones. It always made me a little nervous, I could not help imagining that the conversations they were having were something like, "Hey, I’ve got an American in my cab! Where do you want to meet me so we can kidnap him!"

My third day in Kabul I finally swallowed my pride and paid for a tour of the city. I have always been a little stubborn about this. I rarely ever do guided tours and I usually have a bit of an attitude about this, which is really stupid. I think I miss a lot by not taking guided tours. I do like the experience of wandering around a city and discovering it at my own pace, but Kabul was not the best place for that sort of independent exploration. The tour was arranged through my hotel. My guide and driver was Actar Gul, a retired police officer who now worked for Mustafa's. Actar had lived in Kabul all his life except for a few years as a refugee in Pakistan during the Taliban era.

Our first stop was Darulaman Palace, once the home of the former Afghan king Zahir Shah. It lay on the outskirts of the city. The drive out there took us past many ruined city blocks. Actar shared some stories of harrowing trips to this part of the city during the civil war. He would have to take trips here with his son to buy food for the family. Darulaman palace was still standing, but was a gutted shell. Nearby was the former Canadian Army compound, which recently had been handed over to the Afghan army. The grounds of Darulaman were closed to the public because it had been used by terrorists to stage rocket attacks on the compound when the Canadians were still using it. Nearby the ubiquitous fat-tailed sheep were grazing on the grounds that were once the exclusive royal domains.

Following Darulaman we moved on to Babur's Garden. The drive took us through many more ramshackle neighborhoods, barely better than shantytowns. Despite the meanness of the buildings there were encouraging signs. There were many new schools and saw a lot of school children. Hopefully they can look forward to brighter future that the one their parents have known. Even during the better times in Afghanistan’s past this was a painfully poor country. Actar told me that when he was a boy his family was so poor that for food all they could afford to eat each day was a single piece of the large naan bread, which they would cut into six pieces, one for each member of the family.

Babur's Garden was actually still under construction when I visited. I am not even sure it was open to the public, but I was not going to have another chance to visit. Babur was the founder of the Mogul empire which would eventually encompass Afghanistan, eastern Iran, all of Pakistan and much of India. Although he ruled a vast Empire his heart was always in Kabul and he was buried here. The gardens were on the frontlines during the civil war and were totally destroyed. They are now being restored and by what I saw will be beautiful when fully restored.

The photo of the workmen is an attempt at selective photography gone awry. When I was taking photos in Afghanistan I was usually more interested in the traditional side of Afghanistan, ignoring the modern face of the country. The two old workmen saw my camera and wanted me to take a photo of them. I thought this was great, they were traditionally dressed and had these really interesting weathered faces, I expected a good photo. However before I could get a shot they called over a couple of the younger workmen who were dressed in more Western style clothes. Damn, there went my shot.

All around Kabul the lower reaches of the hill sides were covered with homes, of varying quality, but obviously the residences of the poorest citizens. Actar said that the poor live on the hills where there is no running water or sewage. He was surprised and amused when I told him that in America homes on the hill side are expensive an only the wealthy live there.

The next stop was the Bala Hissur; once a huge fortress and the home of the Amir, it was destroyed by the British and only a few sections of walls remain. Its location remains strategic and much of the site is used by the Afghan army and is off limits to tourists. Actar drove me around to a backside of the Bala Hissur, the only area where photos are allowed. He told me that the neighborhood is bad and it would be unwise to come here on my own. For me even seeing this small ruined bit was powerful. The Bala Hissur features prominently in my novel and is the setting of much of the events of the first half of my story. This was one of those places where I had an "I can’t believe I am here" moment. While taking photos of the fortress I saw a couple of women in blue burquas walking up a road that runs by the fortress. I thought it would make a great photo, the two women framed by the Bala Hissur on the right and a village on the left. I knew I was not supposed to take photos of women, but I thought I could be discreet about it and sneak a shot while appearing to take photos of the fortress. I was not fooling anyone. Actar gently reprimanded me in a fatherly tone. "No picture, woman," he said.

Following the Bala Hissur we moved on to the Mausoleum of Nadir Shah. On the drive up to the mausoleum we passed through some of the most devastated areas of the city. There was one gutted shell of a building after another.

The Mausoleum of Nadir Shah, a monument to a former Afghan king, was badly damaged, but still standing. Actar said that the monument was damaged during the civil war. It was situated on a hill with a commanding view of Kabul. During the civil war the warlord Dostum positioned his tanks up here facing north to the hill Bemaru on the other side of the city where the Commander Massoud had positioned his tanks. From these heights they shelled each other and the city below. To the south past the Bala Hissur Actar pointed out a hill where the Taliban and their Arab allies had taken up positions for their attack on Kabul.

Our last stop was not to any monuments, but to Actar’s favorite kebab shop, run by a childhood friend of his. I do not think they get any Westerners there. I got a lot of stares when I entered, but the food was good. We had mantu and kebab with the usual side of naan bread, all washed down with green tea. Lunch was on Actar, he would not hear of me paying.

Before I left home I often heard the suggestion that I grow my beard and go in disguise. At the time I scoffed at that idea, but it is not really that unreasonable a suggestion. For me it might be a stretch to think that I could disguise myself as an Afghan, but for a white person with dark hair, particularly someone with a Mediterranean complexion it is not at all impossible to affect a credible Afghan disguise. Many Afghans look European. On both sides of the border I met locals who at first looked European; some even with dark blondish hair, but for their shalwar kameez and obvious local mannerisms I would not know they were Pakistani or Afghan. An American freelance journalist, Caleb Schaber (of German ancestry), I met had grown a full beard and often went about in shalwar kameez. He told me that he often had trouble convincing people that he was not Afghan. Generally though this disguise will only fool native Afghans at a distance. However, this has the effect of lowering your profile as a target. As Caleb explained to me, "A lot of the attacks on Westerners are with IEDs [Improvised Explosive Devices]. They set them on busy roads and some guy is waiting around with a cell phone to set it off. If they only see a guy who looks like a Afghan in the car they’re going to hesitate long enough."

In the photo is Andrew, a graduate student from New Zealand, who was trying on his new shalwar kameez.

There is that question, "Is Afghanistan safe?" All I can say is I was able to travel safely, but my freedom of movement was limited. I did not go out at night and I did not travel anywhere without finding out information about the current security situation from reputable sources. There are some parts of the country that are absolute no-go areas like Kandahar and Helmund provinces and much of the mountainous boarder region between Afghanistan and Pakistan. These areas are still active war zones.

Going into this journey I viewed it like a mountaineering trip. You can climb mountains, nobody is going to stop you, but you have to accept that there are dangers. You can manage the risks and most likely you will be fine, but at anytime something could go horribly wrong. Also like a mountaineering trip you have to be willing to turn around at anytime. No matter how close you are to the summit you have to be willing to turn around if it is too dangerous. At any point in my trip I was prepared to turn around and call it quits if I felt it was too dangerous.

That said things are getting better in Afghanistan. Kabul is relatively safe, and by a large consensus the north of Afghanistan is safe. All my experiences with Afghans I met were positive. They are as friendly and hospitable as they were reputed to be. It will be years before Afghanistan is ready for mainstream tourism, but an adventure traveler who is willing to accept the risks can travel here in relative "safety".

Here are some extra photos about the food. This is the naan bread that everyone eats in Kabul. Where ever there are restaurants there is usually a bakery nearby. The bread is fresh. Many times the bread served to me was still warm by the time it reached my table.

This is a very typical kebab shop. In the case they have racks of premade skewers that the cook whips out on to the grill. The grill is a trough of charcol that the cook stokes with a small reed fan. The kebabs are straight from the grill when they are served.

This is Pilau, a dish of rice cooked in sheeps fat, with raisins and carrots. There is ususally some sort of meat with it too. At this restaurant I was also given a side of yougurt to dish onto the rice.

When we got to the actual border we all raced so as not to miss the beginning of the ceremony. There are large grandstands build on both sides of the borders. This is a big spectacle and draws capacity crowds everyday. Typical of Pashtun hospitality, when I went to pay for my ticket, the guys I rode with paid and would not hear of me paying. The grandstands were already full when we got there, but as a foreigner I got special treatment. I had to say good by to the guys I got a ride with as I was ushered forward to special seating for foreigners near the front with good views. Like the bus ride the seating was segregated by gender, the seating on the opposite side from where I was reserved for women.

When we got to the actual border we all raced so as not to miss the beginning of the ceremony. There are large grandstands build on both sides of the borders. This is a big spectacle and draws capacity crowds everyday. Typical of Pashtun hospitality, when I went to pay for my ticket, the guys I rode with paid and would not hear of me paying. The grandstands were already full when we got there, but as a foreigner I got special treatment. I had to say good by to the guys I got a ride with as I was ushered forward to special seating for foreigners near the front with good views. Like the bus ride the seating was segregated by gender, the seating on the opposite side from where I was reserved for women. The ceremony had not started yet, but patriotic songs were being blasted from loudspeakers and there were two cheerleader men in green uniforms carrying large Pakistani flags running up and down working the crowd, getting everyone riled up shouting patriotic slogans. Similar things were going on, on the India side of the border.

The ceremony had not started yet, but patriotic songs were being blasted from loudspeakers and there were two cheerleader men in green uniforms carrying large Pakistani flags running up and down working the crowd, getting everyone riled up shouting patriotic slogans. Similar things were going on, on the India side of the border.

The actual ceremony is just ludicrous. Soldiers from both sides march up and down making these huge silly goose-step marches, lots of dramatic arm waiving, glares, and shouts. It immediately brings to mind that old Monty Python sketch, The Ministry of Silly Walks. The crowd eats it up, and they shout enthusiastically in support of their soldiers. At the end the national flags are lowered in just such a way that one is never lower than the other at anytime. Finally the gates are banged shut and the soldiers march away solemnly carrying the flag of Pakistan, all the while being applauded by the audience.

The actual ceremony is just ludicrous. Soldiers from both sides march up and down making these huge silly goose-step marches, lots of dramatic arm waiving, glares, and shouts. It immediately brings to mind that old Monty Python sketch, The Ministry of Silly Walks. The crowd eats it up, and they shout enthusiastically in support of their soldiers. At the end the national flags are lowered in just such a way that one is never lower than the other at anytime. Finally the gates are banged shut and the soldiers march away solemnly carrying the flag of Pakistan, all the while being applauded by the audience.